In a 1926 manifesto, Kazimir Malevich identified the use of geometry in modern abstract painting as achieving “the zero of form.” This phrase not only describes the absence of recognizable subject matter but also suggests the process of minimizing a composition based on essential pictorial elements. Malevich believed that pure abstraction could provide a departure from the objective world and “concrete visual phenomena,” arriving at art’s intrinsic abstraction and its reliance on “feeling” as a determining factor.[1]

The Russian artist’s theories directed the development of geometric abstraction throughout the twentieth century, and continue to be relevant today. Whereas geometric principles have been explored throughout the history of art, modern painters utilized abstraction in new ways, limiting their compositions to interactions of color, shapes, and lines while rejecting illusionistic space. Once this representational device was set aside, abstraction became a means to investigate how the properties of painting are perceived, establishing the work of art as an autonomous object and subject.[2] Over the course of several decades, and in response to the dominance of Abstract Expressionism, nonobjective art grew to comprise various styles of painting.

Perhaps the most important development to result from what Clement Greenberg referred to as “post-painterly abstraction” is its emphasis on form, which supersedes the identity of the artist. In Europe, individual painting styles were central to art since the Renaissance. Mid-century movements of geometric abstraction, such as hardedge painting and Op art, called for flat, carefully constructed compositions where sharp lines and saturated color are distiniguishing features.

Artists living and working outside of Europe and the United States were engaged with the evolution of geometric abstraction as it occurred, although many had previously absorbed its fundamental properties by way of local visual cultures, including the anonymity of the artist’s mark that often results from nonobjective designs. In South America, for example, pioneering artists in the first half of the twentieth century looked to trends in Europe—where many worked during the early part of their careers—while also delving into the “symbolic imagery and nonobjective language” of indigenous cultures.[3] Their aesthetic experiments were based on “non-objective sensation,” as Malevich first proposed. A number of Latin American painters and sculptors such as Uruguayan artist Joaquin Torres-Garcia worked with the social potential and universal characteristics of geometric abstraction in mind, reevaluating traditional forms alongside the lineage of movements such as Suprematism, Constructivism, and De Stijl.

In the Arab world, painter Saloua Raouda Choucair held the first exhibition of modern abstract art with a 1947 solo show at Beirut’s Arab Cultural Centre. During a stay in Paris between 1948 and 1952, the Lebanese modernist appropriated the mathematical structure of Islamic art as the basis for nonobjective compositions, and contributed to an influential school of French post-war painting. Choucair’s theoretical treatment of geometric abstraction included explorations of space in consideration of social organization; and in the tradition of Islamic art, she argued that abstraction is a method of distillation, one that allows for the essence of matter to be revealed.[4]

Other artists of the time similarly approached geometric abstraction with a critical eye. Like their Latin American counterparts, a major source of inspiration among twentieth-century Arab painters and sculptors was local visual culture. Islamic art and architecture, Arabic calligraphy, and the geometric designs of ancient art were widely used as prompts by regional artists, many of whom recognised the influence of such imagery in the works of modernist pioneers like Paul Klee and Henri Matisse. By the late 1960s, diverse image-makers were working with abstraction across the Middle East and North Africa. Although the first attempt at incorporating Arabic letters is found in a 1944 work by Iraqi painter Madiha Omar, subsequent artists belonging to the modern Hurufiyya movement reinterpreted calligraphy with the aim of collapsing its forms. Mahmoud Hammad led a group of Syrian painters that used Arabic text as the starting point for abstract compositions in which overlapping shapes and color create multiple planes and freestanding letters seem to float due to immeasurable spatial depth.

The breakthroughs of the Hurufiyya movement quickly led artists to take up the international experiments that were redefining nonobjective art. Iraq’s Hashim al Samarchi adopted an approach to abstraction that extends the conceptual aims of Op art by drawing inspiration from illuminated manuscripts of the Quran. Elsewhere, Moroccan artist Mohammed Melehi fashioned a hardedge painting style that reflects the advances in color theory that first circulated in the United States, where he studied, after the release of Josef Albers” Interaction of Color (1963). Melehi’s color field compositions contain wave-like formations that describe springs of energy and movement. Composed of broad lines, his recurring motif is identified with modern takes on Arabic calligraphy, among other sources of regional culture.

Today, a number of the Arab world’s foremost painters continue to work with geometric abstraction, while a new generation has embraced the transnational progression of the movement, casting an even wider net. As a leading member of this emergent group, Sharjah-based painter Mouteea Murad has exemplified its forward-thinking spirit. In the last ten years, Murad has worked through the history of geometric abstraction as he renews its main facets, particularly the plasticity, relativity, and psychological effects of color.

At first, color served as a distinguishing characteristic, a way to break with the expressionist school of painting that has dominated the artist’s native Syria for six decades. Before turning to geometric abstraction in 2007, Murad worked in an expressionist style that he honed at the Faculty of Fine Arts, University of Damascus, where he trained with figurative artists Abdulrazzak Al-Samman and Abdul Manan Shamma, and allegorical painter Khouzaima Alwani. Some of Murad’s colleagues at the university were Reem Youssef, Tammam Azzam, and Mohannad Orabi, who are now recognised for initiating new approaches to representational art. After graduating, Murad regularly exhibited with regional galleries and became known for dark works that depict sullen figures in a black, white, and grey palette. This was followed by a period of formalist compositions in which he experimented with the expressive qualities of calligraphy while also reexamining the basics of figuration. As color disappeared from his paintings, he became engrossed in sociopolitical themes, depicting a world of greed, violence, and exploitation. Murad refers to this period of his work as expressive and critical of “tyrannical injustices.”[5] The dispiriting subject matter of these works eventually took a toll on the artist, posing an existential crisis.

Shortly before entering the Shabab Ayyam competition for young painters, Murad suddenly abandoned his expressionist aesthetic and its outward social commentary, opting instead for vivid color schemes and nonobjective compositions. Part of his motivation for beginning anew stemmed from the experience of working with children at a private school in Damascus, where the creative process of art was heightened by a sense of wonder.[6] In one particular exercise focusing on color and geometry, Murad was reminded of an important aspect of painting: how formal elements must relate in order to create a balanced image. Later in his studio, he made abstract pictures in which different hues were introduced according to the imagery that resulted from collaging the works of his students. Over the bottom layer, he painted loose forms, including expressive lines of various widths and lengths and interlocking shapes that are fluid or defined. The Shared Toys (2007) is the first signed painting from this yearlong project, which he submitted to the competition. The mixed-media work comprises a grid of appropriated drawings that is visible beneath a richly painted surface, resembling a stained glass window or a mid-century mosaic.

In a subsequent untitled painting, Murad’s ornate use of geometry is more pronounced, as the dripped, calligraphic lines seen in earlier paintings have become secondary details that accent the implied movement of dense areas of color. The work contains three stratums: an undercoat of splattered paint that forms an abstract expressionist base; a carefully composed arrangement of triangles, quadrilaterals, and half circles that brings to mind Mahmoud Hammad’s suggestion of infinite space; and a superficial field of sporadic marks. Together, these surfaces create sensuous chaos. Other compositions from this period lean towards the New York school of abstraction with gestural brushwork.

Murad’s investigation of interlocking shapes and contrasting hues continued with paintings that limit the viewer’s perception of depth to a single surface, and emphasize color in order to “transmit” energy and emotion to the viewer. In The Magical Carpet (2008), tightly assembled forms make it difficult to discern between positive and negative space, an elimination of the boundary between foreground and background that results from the artist’s use of evenly distributed solid color and hardedge lines. The work is mostly composed of rotated polygons. This uniform image recreates the sensation of watching an object in motion, as the shapes appear to turn clockwise. Here, Murad is “feeling through color—and not with structure” as Michael Fried observed in the color field paintings of Kenneth Noland. According to Fried, this led the Washington Color School artist to “discover structures in which the shape of the support [or the stretcher] is acknowledged lucidly and explicitly enough to compel conviction.”[7] Murad’s investigation of color relativity—what Josef Albers defined as “the mutual influencing of colors,”—quickly progressed to a consideration of the physical nature of the painting, as an independent object.

.jpg) [Mouteea Murad, The Magical Carpet (2008). Image copyright the artist.]

[Mouteea Murad, The Magical Carpet (2008). Image copyright the artist.]

Paintings such as Festival (2008), Colored Maze (2008), and Arabian (2008) explore how negative space and the treatment of the canvas as a separate environment can create the illusion of floating compositions. In Arabian, for example, an irregular polygon containing a geometric motif is painted against a black background. The intersecting lines and shapes that cut across this image remain confined to its borders, limiting the “action” of the painting to a space within a space. Although minimalist artists such as Carmen Herrera, Kenneth Noland, and Sol LeWitt used similar formal devices, building on the lessons of Suprematism and the cutouts of Henri Matisse, Murad’s rendering is reminiscent of Islamic manuscripts in which magnificent arabesques are placed in the centre or to the side of the page and surrounded by empty paper or modest patterns that seem to recede into the background. Bringing the historical development of this type of geometric abstraction full circle is the fact that in 1947 Matisse described his fascination with Islamic art by stating: “This form of art, with all its aesthetic components, suggests a greater space, a truly plastic space.” As demonstrated in his cutouts, Matisse was particularly drawn to the negative spaces of arabesques, which he studied from Persian and Arab textiles, Arabic manuscripts, and examples of Islamic architecture in Morocco and southern Spain.

Mouteea Murad, Colored Maze (2008). Image copyright the artist.

While Murad’s The Magical Carpet and Arabian are examples of geometric abstraction, it was not until 2009 that he fully embraced the angular forms and flat surfaces of the movement. Around the same time, he began labeling and numbering his paintings as “trials,” with each devoted to specific experiments, a practice that allows him to determine the efficiency of various techniques and compositional elements. As he researched the formalism of painting, he gravitated towards pictorial strategies that treat nonobjective art as a science. Combining different methodologies, he arrived closer to Islamic aesthetics.

Murad was born in Homs, Syria but spent most of his life in Damascus. There, reminders of its celebrated past as a center for Islamic art and architecture were ever-present. During fourteen centuries of Muslim rule across North Africa and West Asia, the city served as the capital of the Umayyad Caliphate, and was an important outpost of the Mamluk Dynasty in addition to an economic and cultural hub under the Ottoman Empire. As Damascus changed political hands, the city acquired new types of architecture, and local motifs were transformed. The history of the Syrian capital can be traced through its various monuments, particularly mosques, churches, and synagogues, and lesser buildings like former religious schools, hospitals, mausoleums, inns, and homes.

Growing up in Damascus, Murad was intrigued by the geometry of its surfaces, whether belonging to edifices, manuscripts, or ordinary objects. His appreciation of the city’s visual culture was initially from a spiritual point of view. In Islamic art complex mathematical patterns and definitions of space adhere to notions of piety, as repetition, symmetry, unity, and order allude to certain beliefs, such as the infinite nature of divine creation. Color also plays a crucial role in communicating this concept and encouraging contemplation. According to Murad, the mystical nature of the aesthetic shaped his visual memory, and has directed his work since he first switched to abstraction.[8] His experience of internalizing the principles of Islamic art and architecture as he developed an awareness of things is familiar to other painters who were born in ancient Arab cities. In their individual writings, Palestinian artists Samia Halaby and Kamal Boullata have described similar connections to the historic architecture of Jerusalem, where they were both born. Boullata details the ubiquitous presence of “the basic form of the square” in the city’s buildings and decorative arts as “a fundamental geometric unit preserving the matrix of abstraction that constituted a decisive part of [his] cultural memory.”[9]

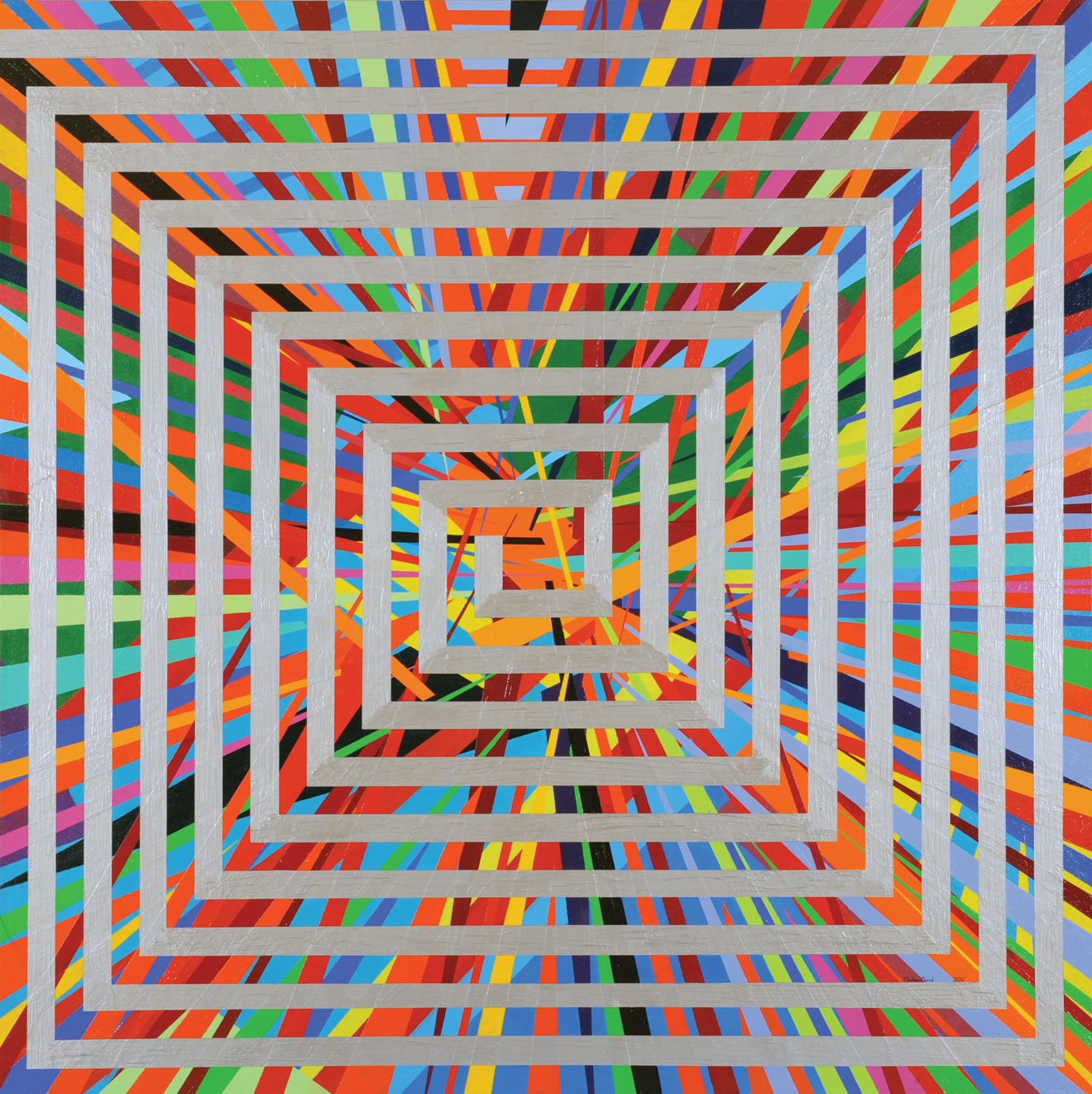

The impact of Islamic art on Murad also materialized as an ongoing exploration of geometric abstraction and visual sensation. The painter intentionally avoids establishing a focal point within the borders of his motifs in order to urge the viewer’s eyes to wander. Consequently, he begins a painting much like an arabesque, and moves towards four equidistant points, developing his composition with the same degree of interest in every direction. Generating a multifaceted motif that seems to blossom outwards, Murad strives for “a continuous kinetic interaction” and considers this aspect of his work to be analogous to “the ornamental units” of Islamic art.”[10] At times a shape or line is repeated as the image expands, for example in Trial No. 11, The Center (2009), where a square in the middle of the painting grows exponentially. Rendered in white, this sequence creates an optical illusion over a colorful composition of triangles that originates from the midpoint but appears to shatter as though made from glass. The grid proposes a centrifugal force that undermines the viewer’s perception of space.

[Mouteea Murad, The Center (2010). Image copyright the artist.]

[Mouteea Murad, The Center (2010). Image copyright the artist.]

Other works show how divergent patterns can be balanced with a method that is similar to the rejection of symmetry in De Stijl painting, where elements are independent yet relative. Piet Mondrian, a leading figure of the De Stijl movement, advocated for pictorial uniformity in philosophical terms by arguing that art is the “plastic expression of the unconscious and of the conscious.” For the Dutch artist, this idea of balance applied to “the totality of our being” in which “the individual or the universal may dominate, or equilibrium between the two may be approached.” In other words, art is subjective and objective, revealing the reciprocal action of the unconscious and conscious mind. [11] Murad sees geometric abstraction as a vocabulary, with formal details functioning as letters that compose words. Together, these details also provide “a mirror of emotions and a reflection of them,” which complete the image for the viewer—a theory that parallels Mondrian’s concepts of equilibrium and “pure plastic expression.”

Works such as Oriental Colors (2009) verify Murad’s reliance on form to retrieve mental images. With an intricate lattice that travels across the composition, the triptych offers a resplendent expanse that reproduces the sensation of traversing different terrains. Sea blue squares, coral and lavender rectangles, and emerald and mustard stripes intersect throughout the painting in a labyrinth of hues. The title of the work describes things that reside in memory but are unnamed, points of reference drawn from Murad’s experiential knowledge reimagined with color. The crisscrossing shapes and lines of his sectioned canvases offer endless passageways for the viewer.

[Mouteea Murad, Oriental Extension (2010). Image copyright the aritst.]

[Mouteea Murad, Oriental Extension (2010). Image copyright the aritst.]

In Oriental Extension (2010), Murad reduces geometric shapes to bands and lines that vary in saturation and density. Although painted according to mathematical calculations, Murad’s stripes achieve what Op artist Bridget Riley referred to as “color-form,” meaning that the structural elements of geometric abstraction are made secondary, as color becomes the primary subject. Oriental Extension contains symmetrical halves that begin at a white vertical axis and continue outwards as a mirrored sequence of lines. Mostly rendered in red hues that alternate in value, the illusion of shifting space is produced through the plasticity of color, which artist and educator Hans Hofmann defined as the “push and pull” of contrasting hues.

The relativity of color became increasingly important to Murad as he developed a body of work that concentrates on the visual effects of lines, a subject that has preoccupied artists since the modern period. One of the earliest exponents of color theory in abstraction was Paul Klee, who referred to his stripes as “strata.” Like a number of artists of the period, abstraction for the Swiss-born German painter correlated to music, particularly the rhythmic qualities of color. Writing on the relativity of color, Klee’s former colleague at the Bauhaus, Josef Albers, later observed that: “As harmony and harmonizing is also a concern of music, so a parallelism of effect between tone combinations and color combinations seems unavoidable and appropriate.”[12] Revisiting these essential ideas, Murad’s striped paintings confirm the ability of color to serve as an affecting detail when hues are placed side-by-side.

In Trial No. 94, Eastern Lines (2013), sections of color appear to move as thin dark bands are dispersed between bright or dull bars. Murad’s motif is made of simple forms, yet the complexity of the composition resides in its changing color combinations, the order of which is carefully structured. The sequences of the painting can be read as a record of time, given that the intensity and thickness of hues change with each stripe, and not one color arrangement is repeated. In a physical sense, the painting’s vivid color scheme, horizontal composition, and long, rectangular shape bring to mind the striped Kilim rugs that originated in the Adana province of eastern Turkey, and are popular across West Asia.

[Mouteea Murad, Trial No. 94, Eastern Lines (2013). Image copyright the artist.]

[Mouteea Murad, Trial No. 94, Eastern Lines (2013). Image copyright the artist.]

Trial No. 94, Eastern Lines belongs to a series of works inspired by the Arab uprisings. Other stripe compositions, however, forgo the geometric precision and color range of the painting. Instead, Murad focuses on variations of a single hue and interposes slightly curved lines and long, thin triangles between bands. This creates the appearance of oscillating forms that descend towards the lower part of the painting, evoking the path of a procession, or the thrust of a society in flux. Murad created the series in Egypt after he was displaced from Damascus by the Syrian conflict. The high intensity of his palette recalls the “strata” paintings of Paul Klee, who based several works on the Egyptian scenery he encountered in the late 1920s. Also present in this dialogue are Bridget Riley’s stripe canvases that were the result of her own trip to the North African country in 1979. During this time, Riley was drawn to the limited palette of Pharaonic tomb paintings. Murad’s images, despite using “color-form,” are closer to the compositions of the German modernist in that they first describe nature when addressing the reality of man.

[Mouteea Murad, Trial No. 121. (2016). Image copyright the artist.]

[Mouteea Murad, Trial No. 121. (2016). Image copyright the artist.]

Recent works by the Syrian artist indicate a return to earlier investigations of geometric abstraction with new insights. In his latest paintings, Murad incorporates the Fibonacci number series as small squares that gradually increase in size over images of crisscrossing bands. In mathematics the sequence is made when a number is the sum of the two numbers before it. The Fibonacci series has been used to illustrate growth patterns in nature, science, and art for centuries. Murad uses the numbers to produce outer motifs that obscure striking compositions, and resemble the latticework of mashrabiya windows. These architectural features provide a view of the street with the guarantee of privacy for the occupants of homes in densely populated cities like Cairo and Damascus. For passers-by, the screen protects an unknown inner domain. In Murad’s paintings, similar geometric grids reveal a world of color and interacting forms through openings that expand depending on where the viewer stands.

*Editor`s note: This essay appears in a new monograph on the artist published by Ayyam Gallery on the occasion of his latest solo show. Curated by Murtaza Vali, Mouteea Murad: Thresholds opens 13 November at Ayyam Gallery Dubai (11, Alserkal Avenue).

Footnotes

[1] Malevich, Kazimir. The Non-Objective World: The Manifesto of Suprematism. Trans. Howard Dearstyne (Chicago: Paul Theobald and Company, 1959).

[2] Seitz, William C., The Responsive Eye. (New York: The Museum of Modern Art, 1965).

[3] Enriquez Schneider, Mary. “Mapping Change.” Geometric Abstraction: Latin American Art from the Patricia Phelps de Cisneros Collection. (Cambridge: Harvard University Art Museums, 2001).

[4] Choucair, Saloua Raouda. “How the Arab Understood Visual Art,” Translated by Kirsten Scheid. ARTMargins Volume 4, Issue 1, 2015.

[5] Murad, Mouteea. A Date with Spring. (Dubai: Ayyam Gallery, 2013).

[6] Interview with the artist conducted by the author, July 2016.

[7] Fried, Michael. “Shape as Form: Frank Stella”s New Paintings,” Artforum (1966).

[8] Interview with the artist conducted by the author, July 2016.

[9] Boullata, Kamal. Palestinian Art: From 1850 to the Present. (London: Saqi Books, 2009).

[10]Interview with the artist conducted by the author, July 2016.

[11] Mondrian, Piet. “Neo-Plasticism: the General Principle of Plastic Equivalence.” The New Art - The New Life: The Collected Writings of Piet Mondrian, eds. Harry Holtzman and Martin S. James. Boston: De Capo Press, 1993).

[12] Albers, Josef. Interaction of Color. (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2013).